Americans want data privacy laws. Well, at least that’s the case since GDPR went into effect in May 2018 and U.S.-based consumers learned about the protections their EU counterparts were now receiving.

States paid attention, and across the country there are scattershot bills introduced and laws passed—all of which will have some national ramification (companies that take steps to be compliant for one state will likely make those changes universal). However, Congress has been slow to act, and for a while, that’s what tech companies wanted. Silicon Valley has been opposed to the California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA), and now they want to be the driving force behind any privacy legislation drafted on a federal level. But should they?

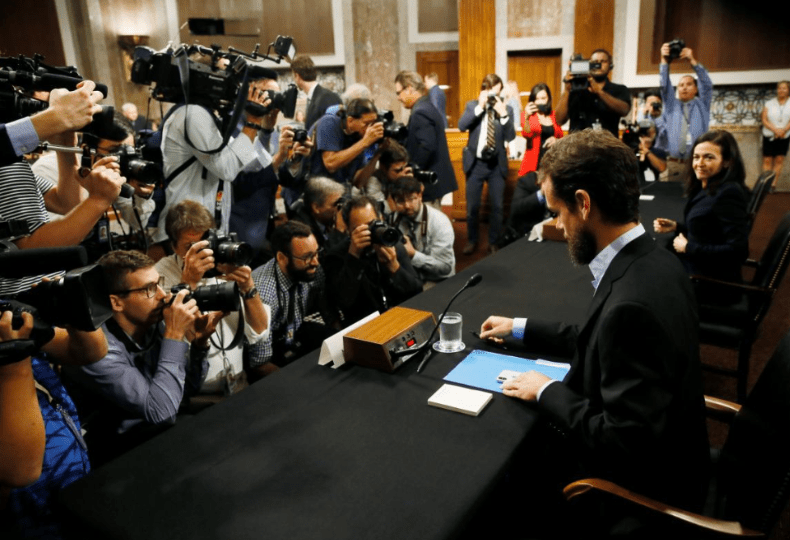

Tech Companies on the Hill

In late September, some of the biggest tech companies — Amazon, Apple, AT&T, Charter, Google and Twitter – attended a hearing on Capitol Hill, testifying before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation about data privacy. The committee wanted ideas on what should be included in a federal privacy act and how much they should draw on the regulations and laws already in effect. The tech companies, on the other hand, came into the hearing with their own ideas of what they want in any privacy law. First, a federal law would need to supersede any state laws. Second, they want Congress to follow frameworks designed by the tech industry, such as the one presented by Google. Many of these tech-offered frameworks already follow guidelines in place by the organizations.

What the tech companies want is the ability to “help Congress craft a federal privacy law without hurting innovation,” CNET reported from a statement from Senator John Thune (SD), chairman of the Senate committee.

Tech companies have traditionally self-regulated when it comes to privacy, and the frameworks they are proposing will, for the most part, allow them to keep doing that. Take the framework Google presented as an example. “This framework is based on established privacy frameworks, as well as our experience providing services that rely on personal data and our work to comply with evolving data protection laws around the world,” Keith Enright, Google’s chief privacy officer, wrote in a blog post and was reported on by The Hill. “These principles help us evaluate new legislative proposals and advocate for responsible, interoperable and adaptable data protection regulations.”

But the real thrust of the tech companies’ efforts appears to be to thwart any of the state-level privacy acts, especially CCPA, and they’ve not been quiet about their opposition to that bill.

“In exchange for volunteering to follow certain guidelines on what kind of information they collect and share about users, the groups said, they would insist that the federal statute nullify California’s rules,” the New York Times reported. The argument is that a “patchwork” of bills would lack the teeth to be effective nationwide, could hurt businesses, and become a regulatory nightmare for both industry and consumers.

Tech Should Have a Voice But How Much?

There’s nothing wrong with tech companies having a say in privacy legislation, but theirs should not be the only voice represented in crafting federal privacy legislation. Instead, we need a balanced process that not only brings in voices from tech, but also from other industries, academics, and consumer interests, according to Tom Gann, Chief Public Policy Officer and Head of Government Relations, with McAfee. “No one interest should have prevalence over the others,” he added. “The legislation should be fair, but that doesn’t mean everybody is going to be happy.”

Steve Durbin, managing director of the Information Security Forum, agreed. “Whilst it is appropriate for there to be some form of consultation regarding the appropriate level of legislation – we need practical, implementable regulations that are fit for purpose – that should not be allowed to drift into the area of corporate gain,” he said. “Privacy legislation should reflect the rights of the individual citizen, not the needs of a large corporation potentially seeking to benefit from the use of data that they have acquired or accessed.”

Nor should a federal law weaken the state laws already in place. Individuals should have the right to understand what companies are doing with their data, and to have more control with respect to ad-based business models. CCPA brought that to California residents, as are laws to Vermont, Illinois, Colorado, and New York to name a few other states that are among the first adopters of privacy legislation, and this right to data privacy is something long overdue to consumers.

Strong state security and privacy legislation has proven itself to be vital for transparency and public trust. It was because of these state laws that we learned of the Equifax breach – because California requires such notification under its breach laws. The idea that a patchwork of laws would be a nightmare is a fallacy because we already see that businesses develop their internal

Tech companies tried to influence CCPA and were unsuccessful. Rather than try to create a federal law to meet their personal interests and frameworks, they would be better off if they incorporate the best aspects of state laws to come up with a strong, effective federal guideline. The last thing we want is a federal privacy framework that is weak and missing the input of the consumer – the people a federal privacy law would most directly impact. Efforts to pass federal privacy regulations should not come at the expense of rendering any enforcement ineffective.

Enjoy this piece? Check out our previous piece in the Need to Know Series: The Indian Personal Data Protection Bill